'Constructing Worlds' at The Barbican. Blog Tour Part 1

‘Constructing Worlds: Photography and Architecture in the Modern Age’ runs at the Barbican until 11 January and, with such a comprehensive range of work to see, this is the perfect holiday season show. Only closed on the 24/25 and 26 December it’s a good excuse to get away from your family for a couple of hours (or, hell, bring them if you’re still speaking to them) and is one of the strongest exhibitions seen in London this year. Over the next two weeks I will be taking you on a multi part blog tour of ‘Constructing Worlds’, looking at some of the photographers and architects in detail.

Installation view showing Hiroshi Sugimoto, Barbican

© Chris Jackson / Getty Images

Bringing together eighteen photographers and eight architects from the 1930’s to present, the exhibition is (as is the usual way with Barbican) organised into a series of alcove mini shows or micro pavilions with wall text dedicated primarily to a single photographers work and then display cases examining architectural context. Each photographer deals with the representation and perception of architecture and, progressing through the show, layers of influence and collaboration are revealed. The viewer is made party to how a whole community of photographers and architects are built from the seeds of each other.

We begin upstairs with America and Walker Evans and Berenice Abbott, the earliest photographers on show both making work in the 1930’s. Evans, of course, was on assignment for the FSA (Farm Security Administration) during this period, undertaking a survey of rural America as part of President Roosevelt’s New Deal initiative. Abbott was on an initiative of her own making, arriving in New York from Paris where her employer and mentor had been Man Ray. She became fascinated by the city and the radical changes that were occurring in the built environment. In 1935 she persuaded the Federal Art Project (part of the Works Progress Administration) to commission her project Changing New York which she described as ‘the past jostling the present’.

Berenice Abbott installation, Barbican

© Chris Jackson / Getty Images

Abbott ended up taking over 1000 images in this series between 1935 and 1939 although on show are several images from her earlier photographic forays into the city such as images of the Rockefeller Centre under construction in 1932. Here we see new social realities playing out in the city as sections are cast into shadow by the dwarfing new sky scraper structures, light and space in the city changed forever. One print, Court of first model tenement house in New York, 72nd Street and First Avenue, Manhattan (March 16, 1936) shows a tangle of washing lines strung up around this pioneering tenement. After a plethora of such types of housing sprung up in the city in the late nineteenth-century, the Tenement House Act was brought into force in 1879 to improve living conditions. In reality, this was a way of trying to artificially rid society of the social problems that went along with tenements; drinking or unemployment for example. Often these model tenements requires occupants to be model examples of society themselves and it was required that a family must have two parents in employment and were screened for any behavioural issues that might upset the tenement as a whole.

Court of First Model Tenement House in New York, 1936. Berenice Abbott

Walker Evans influence, particularly, on the next generation of photographers cannot be underestimated with work from Ed Ruscha, Bernd and Hilla Becher and Stephen Shore all included. While Abbott was documenting the city, Evans was out in rural America alongside other luminaries such as Dorothea Lange and Ben Shahn carrying out ‘special assignments in the field’ and the result was an exhaustive survey of the realities and hardships of tenant farmers and sharecroppers in places like Alabama, Mississipi and South Carolina. Evans was interested in the architecture of the area as much as the people inhabiting them, abandoned farms lost into flood, shaded cabins in Mississipi’s Negro quarter, sugar-cane plantation mansions built by slaves in Louisiana. This series would result in a major solo exhibition at MOMA in 1938, the first ever awarded to a single photographer.

Walker Evans, Frame Houses. New Orleans, Louisiana, 1936

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division,

FSA/OWI Collection [LC-USF342-T01-008060-E]

© Walker Evans Archive,The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Evans also used this early period to perfect his ‘straightforward’ frontal images which are uncompromising yet loving in their gaze. Particularly good to see is his series of churches which have so much personality and reminds of a silly Metro image doing the rounds a couple of months ago – the house that apparently looked like Hitler. Evans interest and protective interest in architecture, preserving them not just in the image but also in real life continued throughout his career. He would go on to publish a controversial nine-page photo essay in 1963’s Life Magazine titled ‘America's Heritage of Great Architecture is Doomed … It Must be Saved’. This essay, featuring images of significant buildings threatened with demolition such as Penn Station resulted in a protest by 150 architects and critics outside the terminus. A key moment although the beaux-arts station would get pulled down regardless.

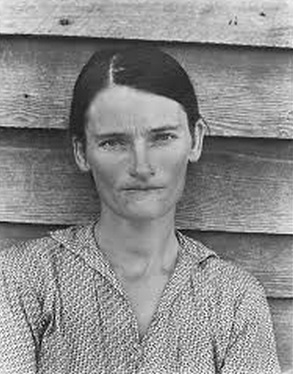

Several images from the Evans section relate to the photographers collaboration with writer James Atgee which resulted in the 1941 book ‘Let Us Now Praise Famous Men’. Evans was seconded to Fortune magazine in 1936 with Atgee in which they lived with several rural farmers and their families in the South documenting their daily lives over a period of weeks. One of the most iconic shots is of 27 year old Allie Mae Burroughs, mother of four and wife of a sharecropper. Evans took four images of Burroughs, all mug-shot like against the clapper board cabin in which they lived. The prematurely aged face, with lips pursed, is concentrated but inscrutable.

Allie Mae Burroughs, Hale County, Alabama. Walker Evans. 1936. Walker Evans Archive, 1994. Accession Number: 1994.258.425 © Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art