Other Animals: An interview with Elliot Ross

This week, continuing the animal theme, we are focusing on the photography of New York-based artist Elliot Ross. Ross has been working on a body of animal portraiture for several years now. When his pet cat died, his wife put up a framed portrait of the animal and this led Ross to thinking about the animals expression, what had the cat been trying to say or express at it looked into the lens and, indeed, can we ever know about an animal’s emotions, thoughts and feelings. This started a photographic trajectory which has endured. In 2010, his publication Animal presented intimate portraits of subjects such as frogs, birds, monkeys and fish and a new collection of Ross’ photography, Other Animals, was published by Schilt in late 2014.

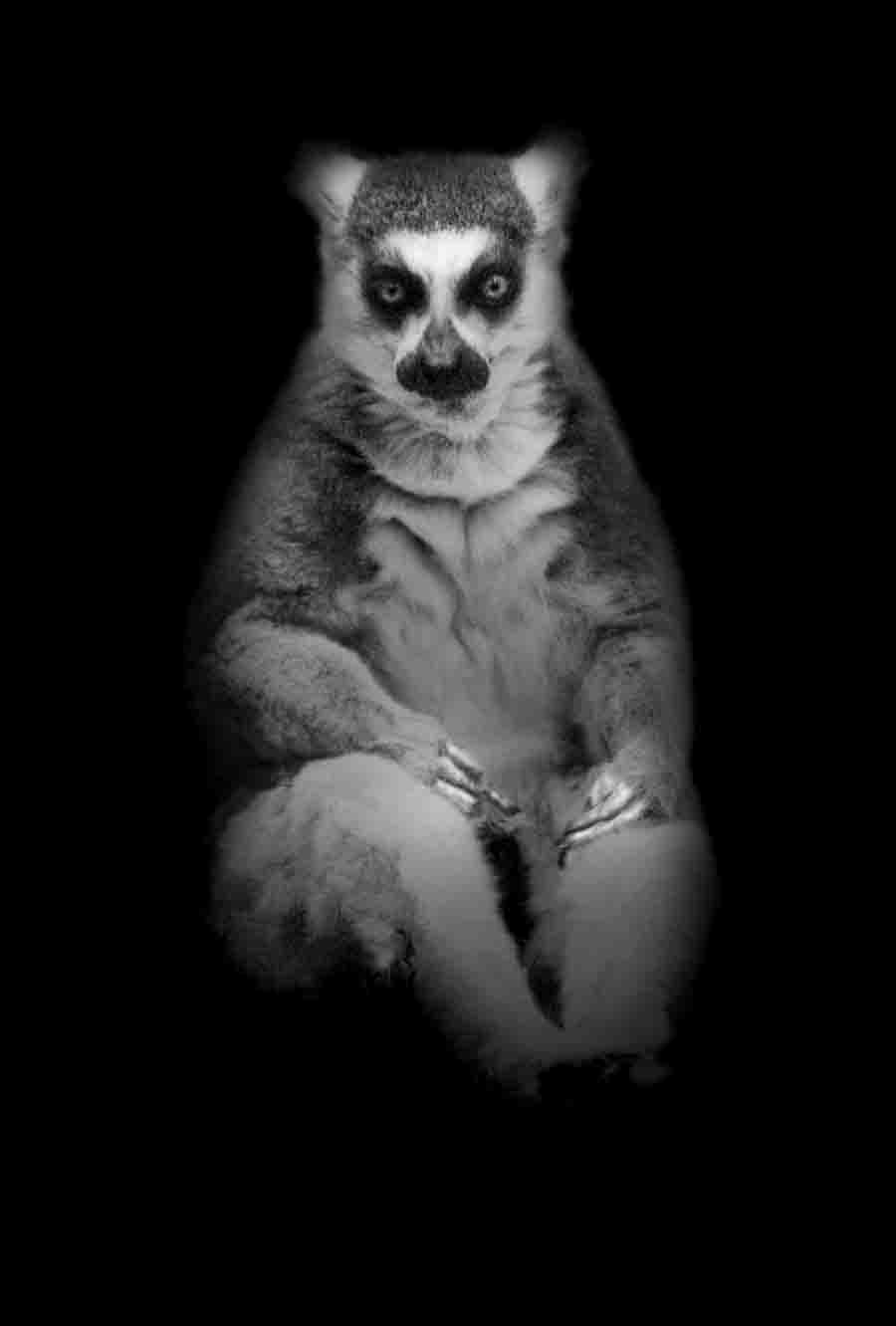

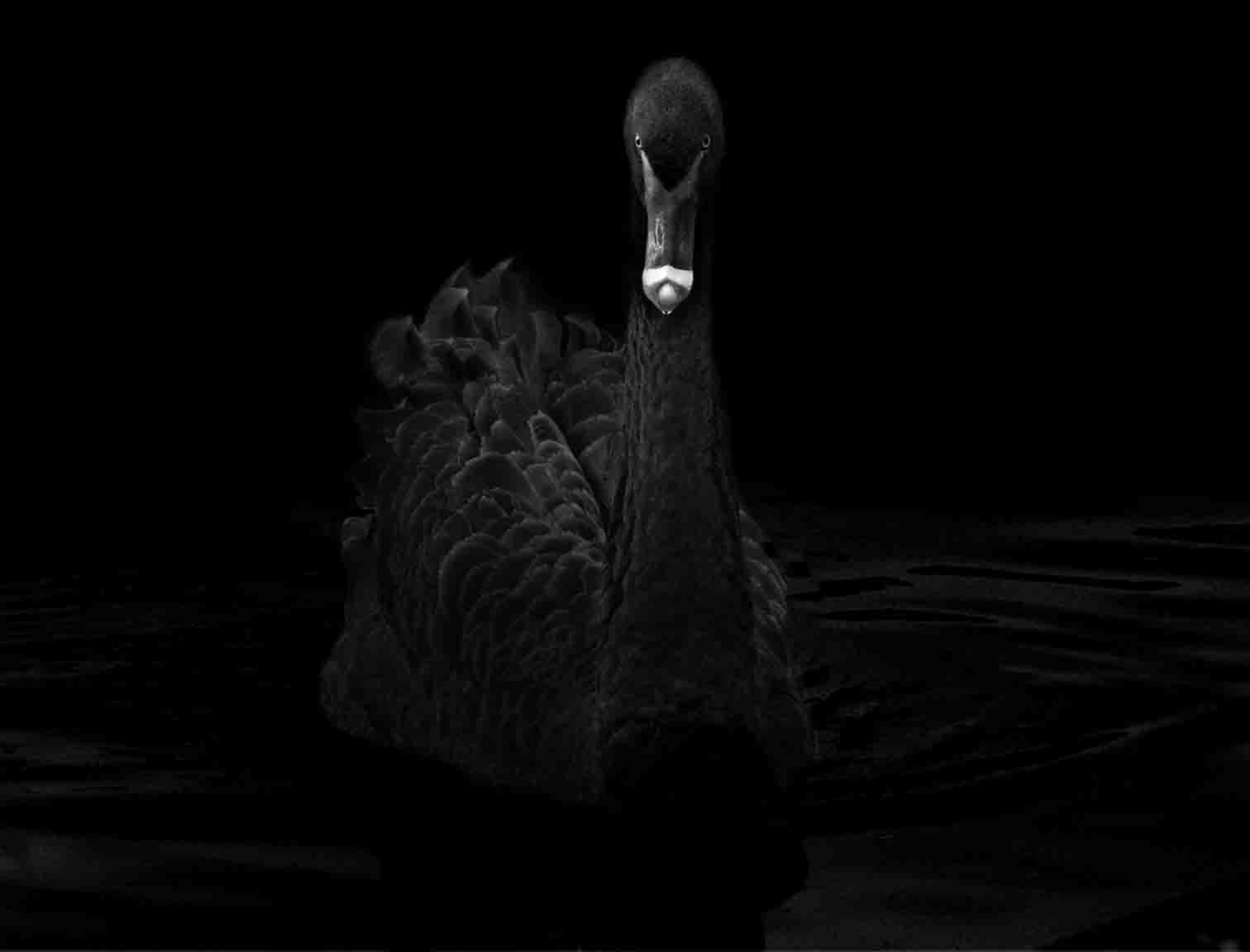

Ross’ animals are photographed, typically, in their normal contexts (whether that be natural habitat, domestic home or in captivity) and then digitally manipulated to create highly dramatic images ‘drawings’ of the animals with details meticulously added, layered or removed during the editing process. Bumphead parrotfish and starfish appear to emerge from a murky black deep; flamingo, gorilla and pigs appear coiffed and good looking, posing for their portrait before accepting the BAFTA, all stylish texture and natural costume.

Ross has not shown so much in the UK, his work was featured as part of the Belfast Photo Festival in 2011 but that has been his last outing this way since. An exhibition is long overdue...

Point102 caught up with Ross over email this month to ask him some questions about his working methods, influences and what he is working on right now...

Point102: What was the starting point for making this type of portraiture?

Elliot Ross: I began the project after our household cat died. I had never lived with an animal of another species before, and was surprised at how close I came to feel to her emotionally. Her loss set off a train of thought that began with this question: How can two beings that are so different share this quality we call animal life?

Point102: And how do you choose your subjects - is this just opportune or do you have animals in mind, ones that may photograph better or have a better personality?

ER: I set out to photograph as many different species as possible. It doesn't matter to me where I find them. What matters is that I am satisfied with what emerges at the end of the process of making the piece.

P102: What is the studio process like, the set up? Can you tell me technically how the images are made?

ER: I don't think it's important that my process be known beyond the fact that I begin with a photograph and end with digital imaging. I will say that digital imaging allows me to work with the photograph in ways that I only dreamed of doing with dark room techniques, ways that are more like drawing, sometimes requiring hours or even weeks of painstaking, pixel by pixel work.

P102: What prompted you to make a follow up of the original Animal’s series - how are they different?

EM: It's not really a follow up but a continuation of the same investigation. There are approximately two million known species alive on earth today; and I felt I had only begun to look at a tiny fraction of them.

As far as the work changing over time, I began to approach the animals that appear in the second book "Other Animals" closer than those in the first book "Animal", and, without going into detail, the range of my digital imaging technique broadened.

P102: What other projects are you working on at the moment?

ER: I am still working with animal species. My latest piece is of an elephant skull. This subject was, without doubt, not alive when I photographed it.

P102: What other photographers work is on your radar at the moment, who are you looking to or back to for influence?

ER: I don't know if I ever would have done pigment prints if I hadn't first seen the beauty of ink on paper in the work of Germán Herrera of San Francisco. But it is to painters that keep returning time and again: Rembrandt, Manet, Sargent, Whistler, Beckmann, Dix, Meidner, and others. Recently I discovered a trove of over 700 works by John Singer Sargent on line and am eager to see the actual landscape paintings I hadn't previously been aware of. It's important to note that I "internalize" the work of other artists. That is, I look intensely at their work, but never try to base my work on theirs.

Animal (222). 2012. Copyright Elliot Ross. All rights reserved

P102: What kind of equipment are you using?

ER: I use a Sony DSLR because of its excellent internal stabilization system.

P102: We usually view portraiture of humans knowing something about the subjects, or if not, projecting history, personality traits etc. - were you ever tempted to go into the story of the animals - their history etc. to provide some kind of context or is it always about the body, the physicality?

ER: I try not to conceptualize my work. Conceptualization leads to the phenomenon that psychologists call “verbal overshadowing" in which the left hemisphere of the brain, which thinks in words, displaces the product of the right hemisphere, which thinks in pictures. So if someone looks at an image I've made of a monkey and believes it looks like a movie idol, that idea was certainly not my intention.

I am constantly reading natural history, biology, and philosophy, and have worked to attain a general knowledge of what humans know (or think they know) and don't know about other animals, as well as what we may never know about them. This factual and theoretical knowledge probably serves to nourish, so to speak, my unconscious mind and perhaps feeds in some ways into my work.

You can see more of Elliot Ross’ work at www.elliotross.com