Development Heaven. George Eksts. University of Hertfordshire Gallery, Hatfield

It is slightly disorientating emerging from the bright and silent, deserted, environment of George Eksts exhibition, Development Heaven, at the University of Hertfordshire’s Art & Design gallery and into the loud emo rock world of the student union. Not ready to go back to the station immediately, I wandered through the campus without seeing a soul. Time seems to have a different elasticity at these more out of the way university campuses – little micro universes all to themselves, the real world seems somehow somewhere else. Given, it is a Saturday afternoon but, I suspect, it might always be a Saturday afternoon in places like this. Perhaps this is appropriate to the work of Eksts. “Time is Eskts' medium” says Exhibitions Curator Annabel Lucas, “He continually plays with it. Time is cropped, edited, lost, suspended, inverted, and reversed”.

Loss, or rather absence, is the first thing to be dealt with within the exhibition – the first work Deuces, produced especially for the show, comprises a sound installation of two people playing tennis and amplified from two speakers placed at opposite ends of the exhibition. I hear nothing but the air conditioning. Following the wire, hoping it will lead to a plug and an on switch, I end up with my hand behind the gallery wall covered in cobwebs. You can imagine, however, what it would sound like. Other works are also not switched on or plugged in and this becomes a bit of a game to figure out which plug needs to switched on to make a particular work get to the point where you think it might be complete. This is particularly true of three projection screens set up flat on armatures with different objects placed on them, titled collectively Land Use (2013). Two are blank black, one covered in pennies and some foreign coins, a strange wishing well, and another with a several weathered cups and glasses -their surfaces limescaley as after too many times in the dishwasher. The third has a moving image of a crowd scene, a fair reception of some kind or perhaps a department store - the figures move about beneath the wooden table leg type object. After some tentative fiddling with the plugs underneath the other two blank screens I manage to make an undulating forest canopy appear underneath the glasses and waves appear underneath the pennies. It’s a little perplexing. The metal tripods the screens are settled on have handles that look very much like microphones and I start to wonder if there is supposed to also be sound which is then being recorded and played back from the underside of the screens. I play with the structures as much as I dare before deciding that these are just part allowing you to be able to adjust the tripods themselves. Maybe.

'Land Use', 3 channel video installation with objects. Photo: Sacha Waldron. Image courtesy of George Eksts and UH Gallery

'Land Use', 3 channel video installation with objects. Photo: Sacha Waldron. Image courtesy of George Eksts and UH Gallery

Another set of works which leave me wondering whether they should have sound or not are five HD video’s arranged in a line along the gallery wall. An open book flaps its pages back and forth in the wind; two figures filmed from behind discuss something in a domestic setting; a wooden sculptural curve rocks back and forth in a gallery; horses exercise in a circular horse walker and finally a theatre sign flashes its glitzy bulbs on and off. The sign is white, unfilled, empty – it both attracts and is redundant. There is something very mesmerising about these works. They emphasis the endless, circular quality in much of Eksts work, often seeming without beginning or end. Does it matter that we never identify the start and finish of these strangers’ conversations or that the horses keep on going round? When looking up these horse exercise structures later I got caught up in watching the aquatic version where the horse swims endlessly in a circular narrow pool, going no-where. So frustrating to not have a direction, an end-point, a journey to be had or achieved.

'The Petrified Forest', HD Video (2011). Image courtesy of George Eksts

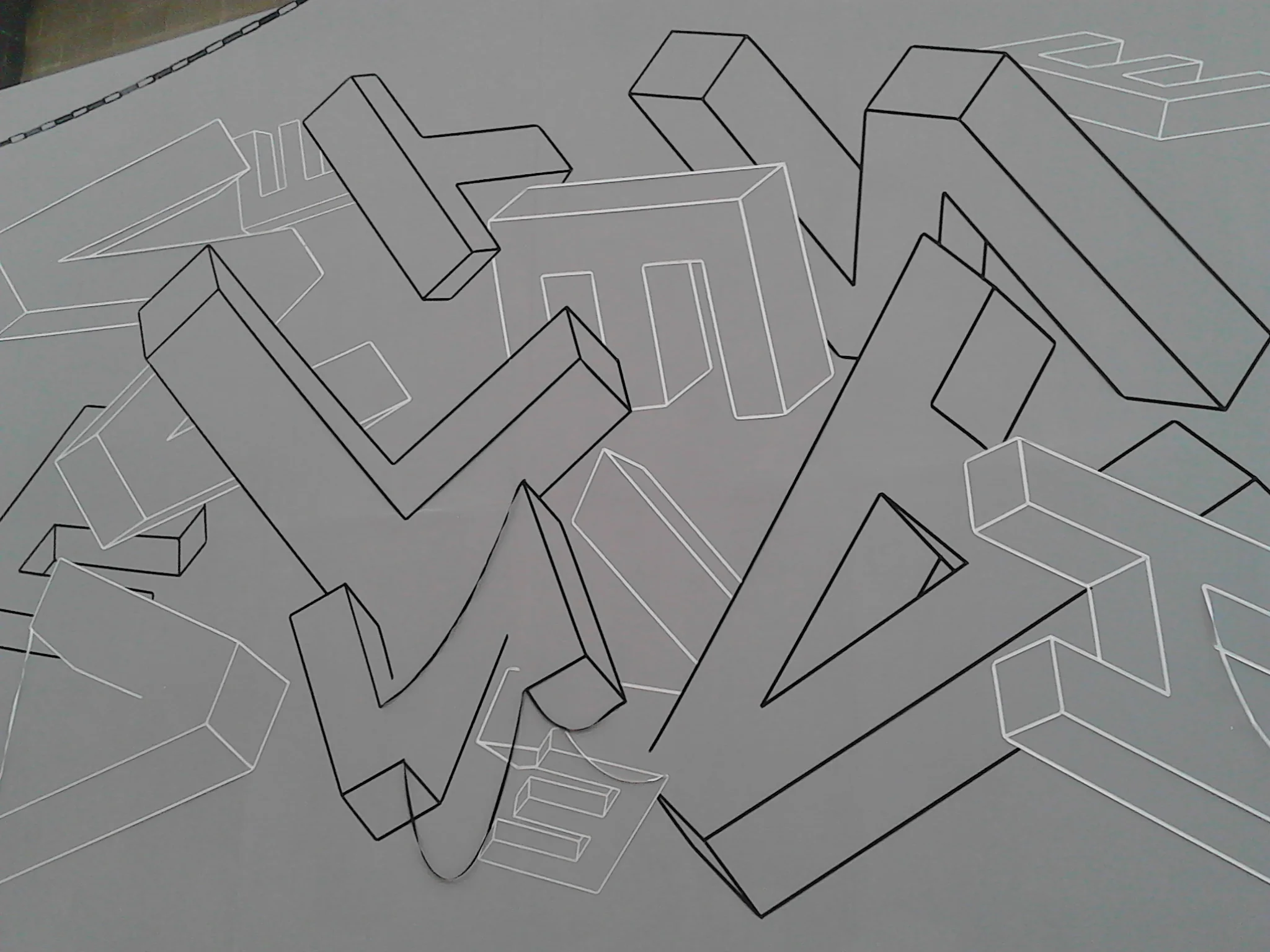

Opposite these screens is the largest work in the room, which does have a very clear end-point - a large wall drawing made from cotton ribbon depicts the letters of the exhibition, Development Heaven, in black and white and mixed up together in a jumbly ball on a grey wall. Over the weeks of the exhibition, Eksts is slowly de-installing this work, the form of the letters themselves sourced from a copyright-free site where unfinished models are offered up to users for completion. The work now exists in a state of suspension - various parts of the thread lines hanging in a draped state of incompleteness, and this mirror the tiny chain link 16mm film reels that are hung throughout the exhibition. I’m not really sure this one works, the chain is too high to really get a sense of what any of the film stills depict and, with the detail obscured, just become a black, white and grey periphery.

'Development Heaven (straight letters only), Wall drawing with cotton ribbon (2015). Photo: Sacha Waldron. Image courtesy of George Eksts and UH Gallery

More successful is the much larger inkjet photographic collage, Catenary Undone (2015) that snakes up the wall at the entrance of the exhibition. A gold chain is set onto a deep black background and provides a striking introduction to the other photographic work in the exhibition. I had to look up the word ‘catenary’ – which apparently refers to the curve that a chain would make under the weight of its own supporting structure. After learning this, I began to think again about the video works in the exhibition - considering whether there was a word for the exact amount of wobble a curve will make when subjected to a particular starting force, a word for the exact centre point between two people’s conversation or the moment when a horse forgets his fist circular rotation and time stops being linear.

Installing Development Heaven. Image courtesy of George Eksts

Smaller photographic works pepper the exhibition and are taken from Eksts archive of research images, often taken from random web searches. These are arranged in small clusters throughout the times. Waves, a stereogram of a black and white column, a garishly lit image of the Coliseum, studio mess and detritus.

Installation view of 'Image Library', collection of found and artist's photographs (2013 - ongoing) George Eksts. Photo: Sacha Waldron. Image courtesy of the artist the UH Gallery

There are connecting threads and complete pleasingly randomness. Curves, chains, studio materials, built structures appear again and again and show Eksts thought-processes, momentary diversions and visual source-material in tiny interesting bite-sized flashes. My favourite image is a diagram showing "All of America’s Olives". It explains that "all of America’s Olives are grown in the West, most of them in Los Angeles planted by missionaries before 1800". The diagram shows an image of the Sylmar grove, one such grove propagated from missionary cuttings along with a size chart from ‘small’ to ‘large’, ‘extra large’ and 'giant'. “Amusing size designations”, the footnote says, “have sensible explanation. The first olives marketed (mission) were classed small, medium, large. Later varieties had bigger fruit, required new terms larger than large, hence the ascending superlatives”. Interesting right? The devil is the detail with these images and they do well to connect some of the dots between works in Eksts complex, confusing, enjoyable and thought-provoking exhibition.

George Eksts: Development Heaven runs at the University of Hertfordshire Galleries, Hatfield until May 9. Open 9.30 - 5.30 Monday to Friday (9.30 - 3.30 Sat/Closed Sunday).

Eksts is represented by Tintype, London.

www.herts.ac.uk/about-us/events/2015/march/george-eksts-development-heaven