Photography Centre at The V&A

V&A Photography Centre –entrance,Gallery 108, with view into The Bern and Ronny Schwartz Gallery © Will Pryce

An exciting addition to the Victoria & Albert Museum, the new Photography Centre is just one in the line up of the museum’s expansion. It came about as a result of the a recent acquisition of 270,000 photographs from the Royal Photographic Society last year. This has doubled the space dedicated to the relatively new art form in the V&A and plans are to double this again in order to showcase as much of the new collection as possible, which now totals some 800,000 photographs and photography related objects acquired since 1852. The centre is only able to display around 600 of this at the moment in its Modern Media Gallery, Bern and Ronny Schwartz Gallery (Rooms 99, 100, 101 and 108).

V&A Photography Centre – The Bern and Ronny Schwartz Gallery © Will Pryce

Initially opened as the ‘Museum of Manufactures’ in May of 1852 at Marlborough House and then ‘South Kensington Museum’ in 1857, the name was finally dedicated to Queen Victoria and Prince Albert in 1899, at the laying of the foundation stone of the Aston Webb building ceremony. During her speech, Queen Victoria remarked "I trust that it will remain for ages a Monument of discerning Liberality and a Source of Refinement and Progress.”

And so it has. Since its early days, the V&A has been at the forefront of presenting wide art education in the UK, from accommodating to the working class by operating late openings to its establishment of the Science Museum.

It was also the V&A that was first in the world to host a photography exhibition in 1858 in its Refreshment upper room-boasting another first; that is, providing such facilities to the public. This major exhibition of the newly established medium displayed 1009 photographs, put together by the Photographic Society of London (now the Royal Photographic Society) and included around 250 contributions from its French counterpart, the Société Française de Photographie.

Although this exhibition was not the great success we may think it would have been, the legacy it set is certainly notable. The Royal Photographic Society, today a recognised charity, ‘realises its objectives through exhibitions and competitions, workshops and courses, a distinctions and qualifications programme, and holds over 500 events across the UK. It also acts as an advocate for photography with the media and government.’

In the beginning, the V&A, or South Kensington Museum as it was known at the time, also held the early collection of today’s Science Museum and it was not until 1914 that the two institutions separated entirely. But the age old debate of art verses science was evident even within this early photographic display as much as it was with photographers of the time. It is in such ways that the V&A invites the public to learn and shape opinions on what art is. This is especially significant when dealing with a form as complex and adaptive as photography that as been so heavily used in all areas of society. Perhaps this review from one writer of the Athenaeum of the time says it best:

'Altogether, whether for light and shade, breadth and dignity, atmosphere and detail, this Exhibition is an advance on the efforts of last year. The artists go on boldly, and are not afraid to be chemists; the chemists gain courage, and long to be artists.'

This is what the new display hopes to show; photography in all its aspects from the tangible early engineering to images as projections that defy the very characteristic of a photograph being timeless.

V&A Photography Centre – V&A Photography Centre – entrance landing, display cases, and camera handling table, Gallery 108 © Will Pryce

There is also a variety of cameras on display specifically for the public to handle as well as a further 150 more in cabinets that serve as an extravagant doorway into the exhibit. Perhaps what sets off our journey through this chronology of photography is William Fox Talbot’s whole-plate camera mounted on its wooden tripod (donated to the RPS in 1921). Regarded as the British inventor of photography, Talbot introduced the fixed image in 1834, marking a turning point for the medium as it made it possible to produce reproductions.

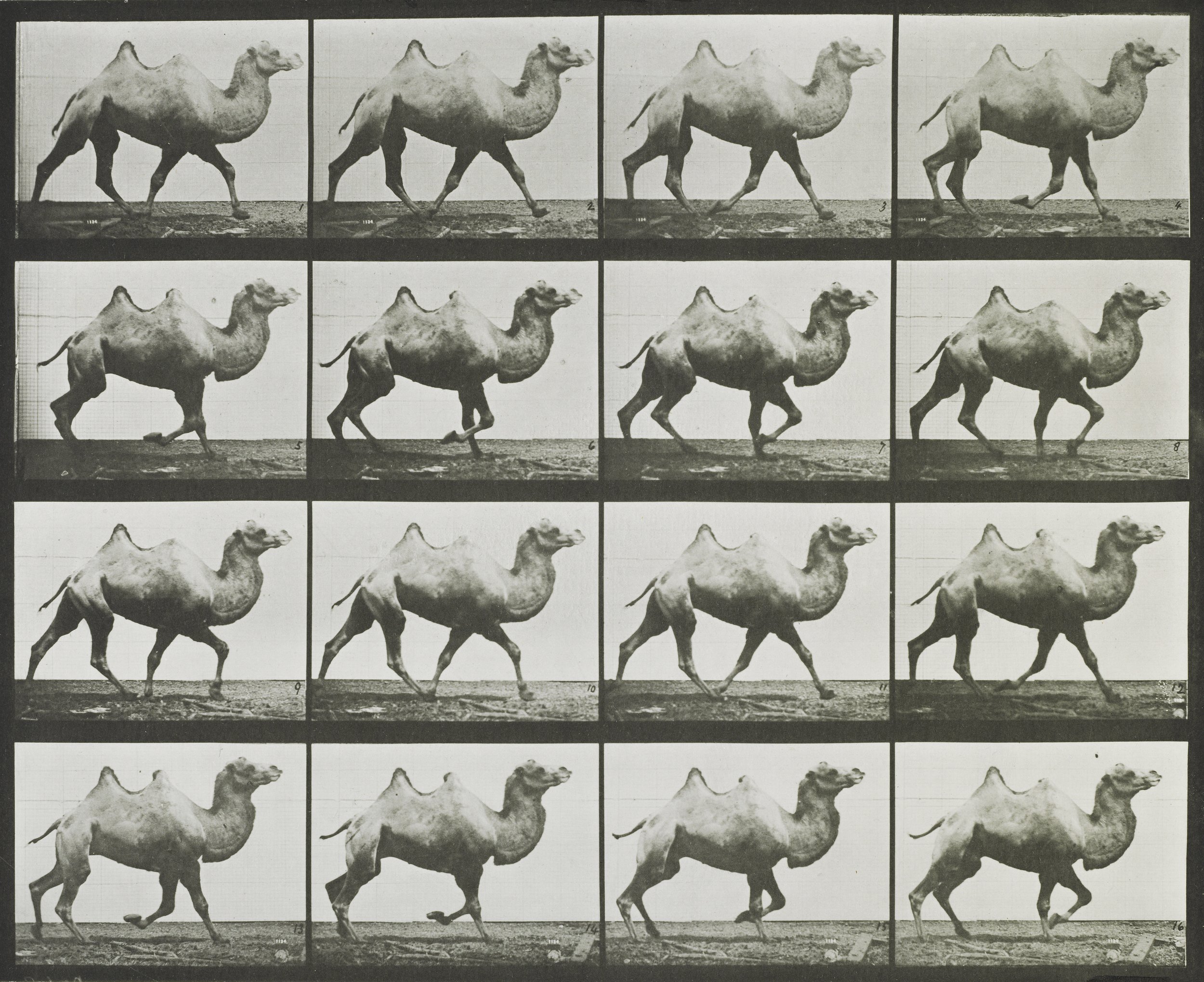

Eadweard Muybridge (1830-1904) Man performing a handstand on stairs 1887 Collotype © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Another notable pioneer in the collection is Edward Muybridge whose used of separate cameras captured the distinct stages of movement; something never seen before by the human eye or in sequential prints. This revolutionary thinking process was further funded by the V&A with the series ‘Animal Locomotive’ and a new standard of photography emerged; the ability to capture various shots of a single motion, giving way to the ideal frame and possibly even the notion of ‘the decisive moment’.

Also among the early photography on display is ‘Festuca Ovina (Rescue Grass) 1854’ by Anna Atkins who adapted Sir John Herschel’s cyanotype process to create the first photographically illustrated published book.

Moving on with pioneering photography, Ernest Payne’s ‘Album of X-Ray Photographs’ is displayed in the collection. Although the first X-Ray images were actually made in Germany by Wilhelm Röntgen in 1895, this photographically conceived invention led to ground breaking discoveries in the medical field.

V&A Photography Centre – interactive stereograph displays, The Bern and Ronny Schwartz Gallery © Will Pryce

Additionally displayed in Room 100 are Sterographs and along with it the possibility of photography used as a popular household entertainment feature. Massively produced transportable devices, the V&A describes them as ‘an early form of virtual reality’ that users could look through to see several images merge together to create a three dimensional illusion.

Four series are on display here: ‘Scenes from La Muette de Portici 1860s’ photographer unknown; ‘Views from Crystal Palace Exhibition at Sydenham Hill, 1855’ by Henry Negretti and Joseph Zambra; ‘Photographic Studies or Studies from Life 1857-64’ by Clementina, Lady Hawarden; and ‘Nagasaki 1859-61’ by Pierre Joseph Rossier’.

Man Ray’s famous ‘Rayographs’ make an appearance as well with ‘La Maison, from the portfolio Électricité’. The photogram process takes that of Sir Herschel’s cyanotype into the darkroom where bursts of light from an enlarger acts as the sun, allowing exposures to be cut down to seconds and sharper silhouettes to be captured.

Another darkroom technique exhibited is solarisation, by Madame Yevonde. This process reverses tones of a photograph by using an initial technically correct and fixed print to act as a negative. This is placed faced down on unexposed paper under a sheet of glass. White, unfiltered light is then shone on and the development of the blank paper shows the original print in reverse.

V&A Photography Centre – Gallery 101 © Will Pryce

The exhibit also contains the contemporary photography from the collection with iconic images from notable photographers like Tom Wood, Martin Parr, Nan Goldin, Cindy Sherman, Sian Bonnell and Hiroshi Sigimoto.

Room 99, The Modern Media Gallery, holds the ‘Light Wall’ which is designed to display screen based photography: a key aspect to any modern photography exhibit (The Photographer’s Gallery has its ‘Media Wall’ to question and inspire the future of the medium in relation to the digital, and with the same intent of showing photography at its new digital era).

At the moment American artist Penelope Umbrico’s ‘171 Clouds from the V&A Online Collection 1630 – 1885’ occupies the multiple screens, showing a transition of 171 images and acting as homage to the notion of photography as ephemeral and intangible once again.

‘The work explores the transition from fleeting clouds to material paint, and then from digital code to physical screen.’

The last section to the exhibition is the ‘Project Space’ in Room 101 where currently German photographer Thomas Ruff has also used the V&A collection to create the series ‘Linnaeus Tripe’. The large photographs on display here are inspired by Linnaeus Tripe’s 1850s paper negatives of India and Burma.

V&A Photography Centre – the Dark Tent, The Modern Media Gallery © Will Pryce

A video loop also runs in the space’s ‘Dark Tent’ explaining the various photographic processes from daguerreotypes and calotype to 35mm slides and Thomas Ruff’s project (Linnaeus Tripe’) using the Paper Negative.

The space is but a glimpse into the archived discipline of photography, where each piece on display carries the medium’s very complex relationship with the world.